Francis Ford Coppola - Up to "The Cotton Club"

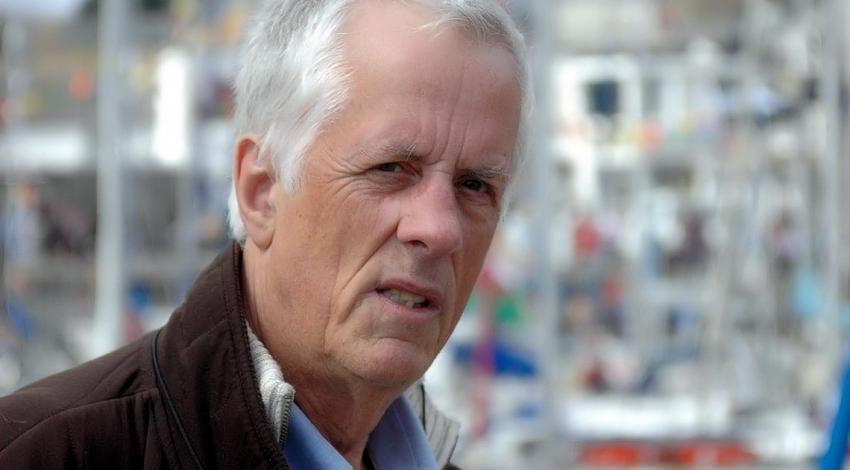

About the Interviewer: Sir Christopher John Frayling (born 25 December 1946) is a British educationalist and writer, known for his study of popular culture. He has had a wide output as a writer and critic on subjects ranging from vampires to westerns. He has written and presented television series such as "The Art of Persuasion" on advertising and "Strange Landscape" on the Middle Ages. He has conducted a series of radio and television interviews with figures from the world of film, including Woody Allen, Deborah Kerr, Ken Adam, Francis Ford Coppola and Clint Eastwood. He has written and presented several television series, including "The Face of Tutankhamun" and "Nightmare: Birth of Horror".

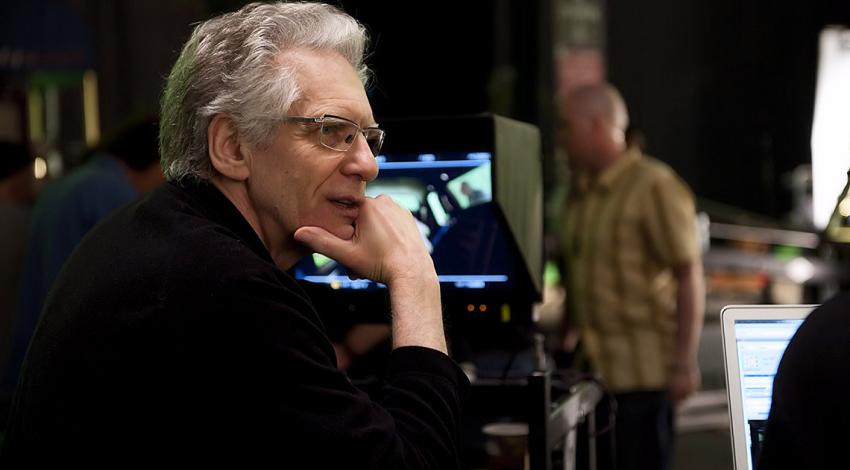

Francis Ford Coppola | Director, Producer, Screenwriter, Composer

You served your apprenticeship originally with Roger Corman working on horror movies. Was that a good apprenticeship?

quote-leftOh yeah. Aside from the fact that it was the only apprenticeship possible, the only way to gain that experience. Nowadays there are many people like Roger making so-called exploitation films. But in those days there was nothing other than Roger, and I was lucky to become his personal assistant, and he assigned me many many different jobs, from editing and writing to being a sound recordist, cameraman - you name it, I did it for him. And although the pay was, of course, very very poor, what you gained in experience and confidence more than made up for it.

And then he gave you the chance to write and direct your own picture, Dementia 13

quote-leftMaking that was a great experience for me. It was really my first feature film, and for the very modest means, it looks like a movie. I had the pleasure of working with some wonderful actors - Patrick McGee, now passed away, was a good character...

Would you count it as one of your movies?

quote-leftOh, definitely. Dementia is my first movie.

Your next film, You're a Big Boy Now, was your masters thesis at UCLA. How did that come about?

quote-leftI was very impressed by things like The Knack and all of those films. I loved the Beatles films when I saw them, and was very interested in the idea of using contemporary music in a dramatic film rather than just in a musical film in the Richard Lester style. I wanted to use some of the energy and cinematic style I saw in The Knack in my story of coming of age.

It's a story of a young man going to the big city. Did you feel it was autobiographical in any way?

quote-leftYeah, I had gone to military school when I was fifteen, and I became very frustrated. I ran away from school and went to New York and wandered around for a good ten days, sleeping where I could and having certain crazy adventures, frightened that my parents were really going to be mad. A lot of the textures in that film were out of experiences that I had then.

Did you feel it was a mature work?

quote-leftWell, it was obviously not a mature work, but it was certainly well put together, and had some imagination and was a good indication that I had worked with actors before in theatre and could stage real scenes with actors. And it had some funny moments. I don't think it was a world-shattering movie, but it had some good things in it.

What did the examiners say when you submitted it as your thesis?

quote-leftAt that point, I had won several awards at UCLA for my writing and was already known for my brash attempt to leap outside of the school confines and really make a feature film. I wanted to make one very badly, and it was very hard to make a feature film in those days. Everyone was pleased that I had done it, and for a few years it set a dramatic precedent at the school.

You then moved on to a really big studio production, Finian's Rainbow, probably the last of the big Warner Brothers big studio musicals.

quote-leftWell, there are some interesting things to know about Finian's Rainbow. One was that I had made a private resolve that from that moment on I would only direct original screenplays, original writing of my own. That was really always my desire and my dream, and in my career I have violated it many more times than I have kept to it. Of course I knew all about Finian's Rainbow and all the Broadway musicals of that era. I can still sing every song from all of those musicals, and do whenever asked! What happened was that it was too thrilling to consider being a director of a big Warner Brothers musical, so I violated my rule and accepted what I thought was this job. In fact, the big musical that year was Camelot, and the idea was that we would make our movie on Camelot's sets.

The show dealt with a lot of racial inequality and sharecroppers from the late forties, and it was very hard for me to imagine doing this stuff on phoney sets at Warner Brothers. I requested that we take the company to Kentucky and find a way to do the old forties Finian's Rainbow in a way that would be relevant in this new sixties that was beginning to have race consciousness in a new way. But of course we ended up doing it for not very much money in the Camelot sets in the way the studio wanted to do it.

I was very unhappy during the production because you didn't get to cast, you didn't get to pick the art director, you didn't really get to edit it exactly the way you chose and you didn't get to do the final post production. Out of my frustration one of the highlights of the picture was when this skinny kid, who was more or less my contemporary, became a friend of mine, and that was George Lucas. We conspired to leave the studio stuff and get little truck and put our cameras in it and drive across the country and make movies in a more personal, artistic way. And so I left the Finian's Rainbow experience and went right into The Rain People with George there.

It seems very ahead of its time now, as a road movie that almost makes itself up as it goes along. Did you have a script to start with?

quote-leftThere was quite a specific script. It was the first of two films that I got to write and make as I had hoped all my films would be. One of the criteria was that it would have a serious subject matter, something about people. One of our heroes in drama school was Tennessee Williams, and we thought of serious drama in that way, so Rain People was written a little with his influence. And yet we took it on the road with a very elastic type of crew that could function anywhere, and as we went across the country we were free to go anywhere - we had no pre-picked locations.

Does the central character learn anything as she goes along?

quote-leftShe was a woman trying to leave any and all responsibility, and finding in the form of this pathetic football player who needed her so much that she couldn't shed the responsibility. It was as though the unborn child she carried inside her could talk to her, saying "don't leave me". And at the end she says to the fellow "Come with us & we'll go back and live as a family." I think I was trying to express some ideas about what basically became women's liberation five years later - trying at once to be sensitive to those issues in a woman that would cause her to want her own freedom and yet at the same time trying to collide them with a sense of family.

It was startling to just see a movie in those days about a woman who gets up and leaves her husband. In Spain, where it won an award at San Sebastian, you should have heard these guys going on - "What kind of woman would do this?" So on one hand it was ahead of its time, and in my opinion it's still ahead of its time because ultimately we will always come to realise that we have to find a way to create families.

When you were offered The Godfather after The Rain People, it must really have seemed like an offer you couldn't refuse

quote-leftWell, it's maybe hard for people to realise now, but in those days The Godfather was in the very early period of its success as a book. It wasn't quite the mammoth book that it became after I had already been given the job, and to me it had a lot of sleazy aspects to it that were cut out for the movie. I didn't like it very much for those reasons, and I was very frightened of getting once again co-opted into another low-budget project. There wasn't much money, and in those days they wanted young directors because they were cheap. So I did turn it down once or twice.

How did you respond to criticism that The Godfather was overly sympathetic in its portrayal of this mafia family?

quote-leftFor the purposes of The Godfather, we took this family and we played by the rules. For example, it was very important to know that Vito Corleone would not deal in drugs. He was a good bad guy. On that level of genre movie-making, there are the good bad guys and the bad bad guys, and it's all right if the good bad guys kill the bad bad guys. So when people talked to me at that time about the movie, I thought that it wasn't different from many genre pictures that on that level dealt with characters that were killers.

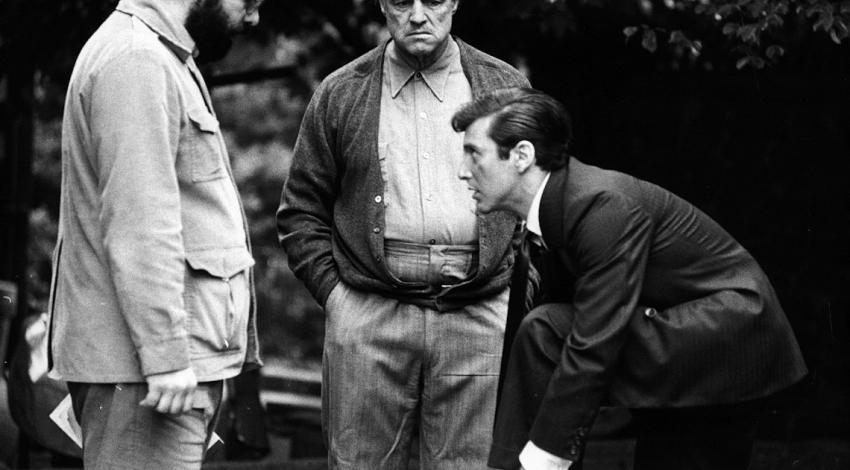

I've always tried to make my films be beautifully acted, and part of making films be beautifully acted is to give it the illusion that it's been worked out on the set, when in fact everything may not have been. And the big success I had on The Godfather in creating all those on-screen relationships came from one dinner I arranged. It was an Italian dinner with a real table and with all the boys - Marlon at the head of the table, Sonny, Al PacinoÉ..they had never met each other before really, and my sister who played the sister in the film served the spaghetti and the wine. And it was just like playing at being together as a family - that kind of sensual opportunity, sense memory, if you like, gave them a way to relate to each other. How to make Hollywood megastars into a happy family.

I was known as an actors' director from many many years further back than I was even known in film. I think I try to give my actors a certain sense of life that comes by using what the actor can contribute. But very often the text is written, it's just that I have the skill and experience to work with actors whereas many directors don't have any experience of that. They sort of give them a script and they say their lines and they stage it somewhat and that's it.

Where did you get the idea for The Conversation?

quote-leftIt started with a conversation, ironically, with Irving Kershner. We were talking about eavesdropping and bugging, and he told me about these long distance microphones that could be used to overhear what people were saying.

A film like The Conversation was only made because I made The Godfather. Nobody would let me make a film like that - that is not the kind of film that seduces an audience. My film, which I don't consider a film about crime, is not the kind of picture that panders to an audience. It's a difficult film.

Your next big film was Apocalypse Now. What image of the Vietnam war were you trying to put over?

quote-leftWhat I most hoped for was to take the audience through an unprecedented experience of war and have them react much as the people who went through the war did - come out being saying "I understand what it is. I don't know if I can say what it is, but I feel I know what it is."

There was an idea from George Lucas and John Milius to do it in 16mm, all very documentary-like, but I would have done it in Cinerama (wide-screen process) if I could. As long as you're going to stage this war, why not get it with all the power and beauty that film is capable of?

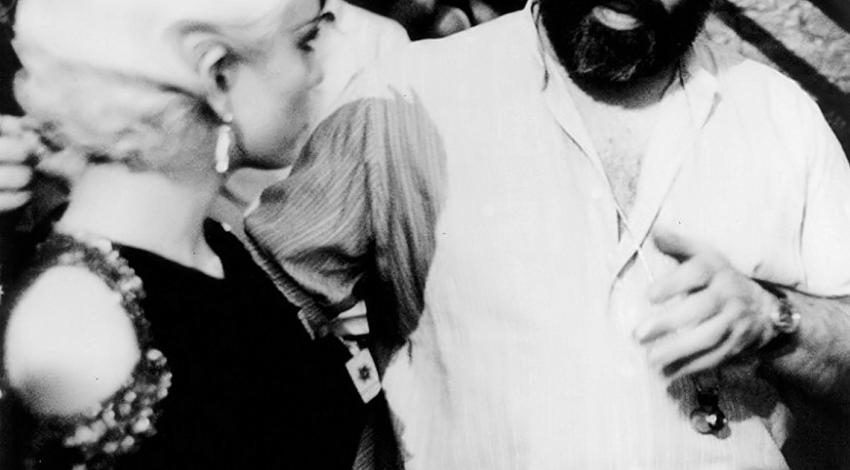

And when you left for the Philippines, you didn't have an ending?

quote-leftWe did have an ending. At the point you could almost say "Enter the press." The press in a new dimension that I never understood before. I always thought that they were the people who were reporting on what's going on. I never knew that they were part of the phenomenon itself, and they were a participant trying to make their own careers out of it. With Apocalypse Now begins a long and probably never resolved disrespect that I have for the American entertainment press. They haunted us on that picture - they were constantly coming though not invited, they gave the impression back home that it was sort of "Apple Records" out there without any organisation. In fact you couldn't do what we did without being organised. It was like being an army out in the Philippines, and this notion of the film not having an ending was and wasn't true, to the extent that something that dealt with those ideas and those themes is difficult to end. It was a film about morality, and of course morality doesn't have any place in the middle of a rough war like that.

Did Brando's arrival affect the way you thought of the ending?

quote-leftWell, as you've probably heard, he arrived extremely overweight, much more so than our agreement with him. He had said he would come at a weight that would let him at some level be believable as a military officer. When he did arrive so overweight, I went to him with suggestions to rewrite the ending so that Colonel Kurtz's sickness, moral sickness as it were, was related to it. I really was in an incredibly tough situation - here I was financing the film myself. After a few days what I finally did was by dressing him only in black and photographing only his face, and by using another actor who was quite tall, try to give him the impression of being almost a mythic giant. And then by using his face - he has a wonderful face and incredible intelligence - to try to have this ending of the movie relate philosophically to certain things that the character had seen. Of course the man was also partly insane.

Can we talk about American Zoetrope and One from the Heart? What were you trying to achieve by starting that studio?

quote-leftI did sincerely believe that the medium was about to undergo a big transition, that it was about to become electronic. And I thought that possibly, if you had a studio of the future that enabled you take advantage of the great illusion making quality of television, we would be able to make serious writing and shows of all types with dimensions that really you had never done before. I wanted to begin to prepare for a future cinema that would basically be a mega television with studio capability. Something that would enable you to do Lawrence of Arabia right in your own back yard if you wanted to.

One From the Heart was of course the beginning experiment to tune up the studio as a whole. My dream was to do hundreds of movies in those studios, and so it was in a way a sampler. It was a simple story, but a story told entirely in song - I wanted to try a story all by song in this very unreal yet pleasant way.

It feels to me now like an exercise in style - I thought it should have been called One From the Machine. There's not a lot of heart in it.

quote-leftWell, there's not a lot of machinery in it. It's basically stagecraft and a kind of musical parable about a couple. It was no more complex than that - it was a little musical valentine.

Why did the experiment fail at that time?

quote-leftIt was a big studio and there were a lot of people and a lot of assistants, and they had assistants, and everybody wanted to make normal Hollywood competitive wages. And the failure of One From the Heart to bring that kind of money in, and the ongoing attack by the entertainment press of the films just made it impossible. At any rate, the place was destroyed financially.

You then went on to make two films based on books from the sixties - The Outsiders and Rumblefish. Why did you decide that the time was right for those films, the mid-eighties?

quote-leftOne day I got a letter from some little kids, kids maybe eleven, twelve. Forty of them signed a letter asking that we buy and make into a film this book by Susan Hinton, The Outsiders. They loved that book, and they wanted someone who would make it exactly the way the book was, and not ruin it the way a lot of film companies do. So we did buy the book, and when the crisis had hit at Zoetrope, there were really two ways for me to go. One was to just shed it all and let go and quit the film business, and the other was to try to fight back by being as productive as possible and making one film after another. I like kids very much and I get along with them, and I thought it would be a real tonic to go off somewhere more Rain People style with a bunch of kids, young boys and a girl, and make the story just for those kids. And that movie was very very successful, it made a lot of money and it saved this company.

Which brings us around to The Cotton Club...

quote-leftFor me, the most interesting part of The Cotton Club was the theme of the black and white, in so far as the club had the most talented black performers of its day and yet it was segregated and black people couldn't go see the show. It was the hoi polloi, the real high society people who went and I wanted to try something with two worlds, a black world and a white world interweaving between each other and of course meeting at the Cotton Club with the numbers and the shows. There was a kind of Wild West temperament in New York in those days, the twenties, and specifically the gangsters were German-American gangsters, and also of Jewish and Irish descent and historically, they were about to be part of turning over the power to the Italian gangsters in the thirties.

How interested were you in historical accuracy?

quote-leftI have worked on several films that have used historical information, learning from the master, Mario Puzo. His technique generally is to take from the press archives and records and court records the real facts of these people, but to fudge a little sometimes in the area of combining two characters into one or sometimes moving things that were really happening in 1936 to 1934. I heard people who had actually been there saying "Is that Lulubellle? That's not her! Oh, that didn't happen that way!" But I feel this really is the tenor of the Cotton Club. Maybe it was a little sleazier than I portrayed it, maybe certain people were treated a little more poorly than I showed it, but the themes that are there - of servitude and a desire to use your talent to break out of that servitude into some sort of white world - certainly, that was the truth.

What about the future?

quote-leftWell, I have great concern and personal feeling about the fact that I have not been able to pursue being a writer and writing original dramatic material. Now that the film industry in our country has been pretty much entirely won over by the interests of the TV mind and the profit syndrome, my dream to write original material and to make it in an inexpensive, and therefore possible, way, got eclipsed.

* © (1984) Adger W. Cowan, Orion Pictures Corp.

** © (1984) American Zeotrope Studios

*** © (1984) Metro Goldwyn Mayer Studios

**** © (1990) Paramount Pictures

Comments

https://www.dga.org/News…

https://www.dga.org/News/PressReleases/2020/200307-DGA-National-Board-Approves-Tentative-New-Agreement.aspx